Grounding research in operational realities: How a novel salmon study advances the toolkit for assessing ecological safety

Today we’re sharing a new peer-reviewed paper in Frontiers in Climate that tackles a practical, and increasingly important, question for marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR): what do real-world operations mean for local ecology? At Project Macoma, a first-of-a-kind pilot project operating in Washington state, we worked with local stakeholders to design and conduct research on how Ebb's operations in Port Angeles might affect young salmon. The results are encouraging: even under the most extreme exposures we found that juvenile salmon showed no adverse effects. Just as importantly, we now have a blueprint for assessing ecological risk at future sites, incorporating the priorities of local rightsholders and communities, and paving the way for responsible deployments at scale.

How Project Macoma works

At Project Macoma we draw seawater from Port Angeles Harbor and treat it on-land by removing acid. The remaining alkaline-enhanced seawater is then released back to the harbor through an outfall system that is designed to ensure rapid mixing with the surrounding water. This process allows the ocean to safely absorb additional CO₂ from the atmosphere while reducing local acidification.

Building the playbook for safe and responsible deployment

Safe and responsible deployment has been a primary focus for Project Macoma. Our guiding principles for this work are straightforward: for mCDR to scale responsibly, we need (1) a deep understanding of local ecology and the communities who depend on it, and (2) methods that help predict ecological impacts under realistic operating conditions before operations begin, so we can mitigate any potential effects.

Novel salmon study methodology

From the beginning, Ebb engaged with the Port Angeles community to inform Project Macoma's design and operations, and to understand local questions and priorities. Through early and ongoing consultation with local Tribes, we identified a priority question to study together: If juvenile salmon pass through the area while Project Macoma is operating, what might they experience—and could that brief exposure cause harm? In the Pacific Northwest, salmon are a keystone species with profound ecological, economic, and cultural importance, making them a clear priority for careful study.

To address this question, we collaborated with the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe (LEKT)—who manage a salmon hatchery along the Elwha River and provided juvenile coho salmon for the study—alongside habitat biologists and environmental scientists at Anchor QEA and Spheros Environmental. Together, we developed a novel "pulse-test" study.

Our approach involved three key steps. First, we used near-field dilution models (standard permitting tools under the U.S. Clean Water Act) to predict in-water conditions near the outfall when alkalinity is being released. For the study published in Frontiers in Climate, we focused on in-water conditions 3-6.3 meters (10-20 feet) from the outfall during routine operations.

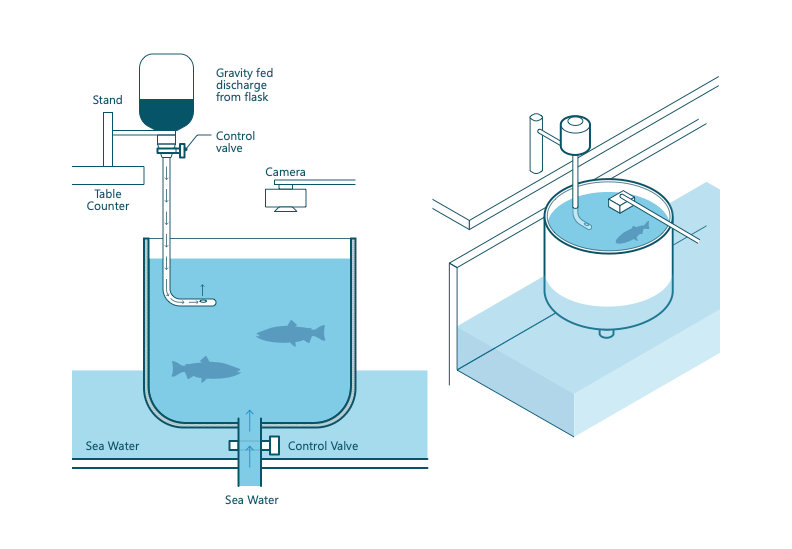

Second, we designed laboratory tests to replicate those expected in-water conditions. Previous studies have exposed marine organisms to sustained elevated pH and alkalinity over many days, but for mobile species like salmon that can swim in and out of the area, we needed to understand potential impacts from brief, transient exposures. We placed juvenile coho salmon into test chambers with fresh flowing seawater, then "pulsed" alkaline-enhanced seawater produced by Project Macoma into each chamber to mirror the forecasted conditions.

We tested three exposure durations: 30 seconds (slightly longer than the time it would take for a juvenile coho salmon to swim past the outfall), 1 minute, and 5 minutes (reflecting scenarios where a salmon might linger to forage or avoid predators). After each exposure, the chamber was gradually flushed with ambient seawater for several hours. Members of the Tribe observed the testing, and throughout the experiments, juvenile coho salmon were continually monitored for behavioral stress signals and checked for physical impacts at the end of each test.

Findings

We performed the pulse exposure tests twice to simulate different operating conditions. The first round simulated routine operations (discharge pH ~9.8) and is described in our Frontiers in Climate publication. The second round, completed in December 2025, simulated scientific operations (discharge pH <12) closer to the outfall (within 2 feet). Both showed consistent results:

- No differences in juvenile coho salmon behavior between exposure to fresh seawater and alkalinity-enhanced seawater

- No mortality in either test case

- No observed physical effects of alkalinity exposure on gills, eyes, or external tissues

- Observations confirmed that fish regularly occupied all areas of the tanks, including near and directly beneath the discharge point, indicating they were not avoiding the alkalinity-enhanced water.

These results give us confidence that Project Macoma is operating safely. But just as important is the repeatable methodology we've developed that can be applied at future sites, adapted for other species, and used by others in the field. This approach is designed to be conducted by commercial toxicology laboratories and is supported by standard mixing analyses commonly required for project permitting.

This study doesn't claim to answer every ecological question about OAE, no single experiment can. What it does provide is something the field of mCDR needs: a transparent, repeatable way to translate expected operating conditions into ecologically meaningful tests, designed in partnership with the people most connected to the ecosystem. Going forward, we hope this work can serve as a practical blueprint for how mCDR projects assess ecological risk.